The Scottish Ambulance Service has conducted a systematic review and developed a large evidence base by examining the toxicity of mephedrone and its metabolites. This publication details the ways in which the toxicity of mephedrone has been studied, as well as methods to reduce harm from mephedrone.

Researchers at Aberdeen Royal Infirmary conducted a critical review of the evidence to investigate the potential effects of taking mephedrone. The study consisted of two parts: the first was a literature review and the second was a retrospective analysis of cases admitted to the emergency department at the University of Aberdeen.

What is mephedrone?

Mephedrone (MCAT, Meow Meow, Bubbles and Meph) are all, as far as those purchasing them are concerned, referring to the synthetic 4-methylmethcathinone. A cathinone derivative that was first believed to have been synthesised and propagated in 2007, it gained widespread notoriety in Israel and Australia. Sweden criminalised possession in December 2008 following the death of an 18-year-old girl who had purportedly taken mephedrone.

On 7 April 2010 the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 (Amendment) Order 2010 was passed, declaring 4-methylmethcathinone and other substituted cathinones class B drugs as of 16 April 2010. This took place under a weight of pressure from the media despite a perceived lack of evidence as to its potential harms.

How was the scientific research conducted?

All scientific information was searched in Medline, Pubmed and EMBASE using keywords. The scientists analyzed the relevant articles and the list of sources. The main observed and described effects of mephedrone, as well as cases of mephedrone overdose and acute toxicity were identified.

We constructed a retrospective, consecutive case series of all patients who reported mephedrone ingestion who had presented to the Aberdeen Royal Infirmary ED from 1 December to 16 April. This was achieved by a manual review of all ED cards for this period. Cases were included when cards described a mephedroneassociated attendance. Cases were excluded when there was insufficient data regarding presentation, mephedrone ingestion was unrelated to the presentation, or there was concurrent ingestion of other illegal drugs.

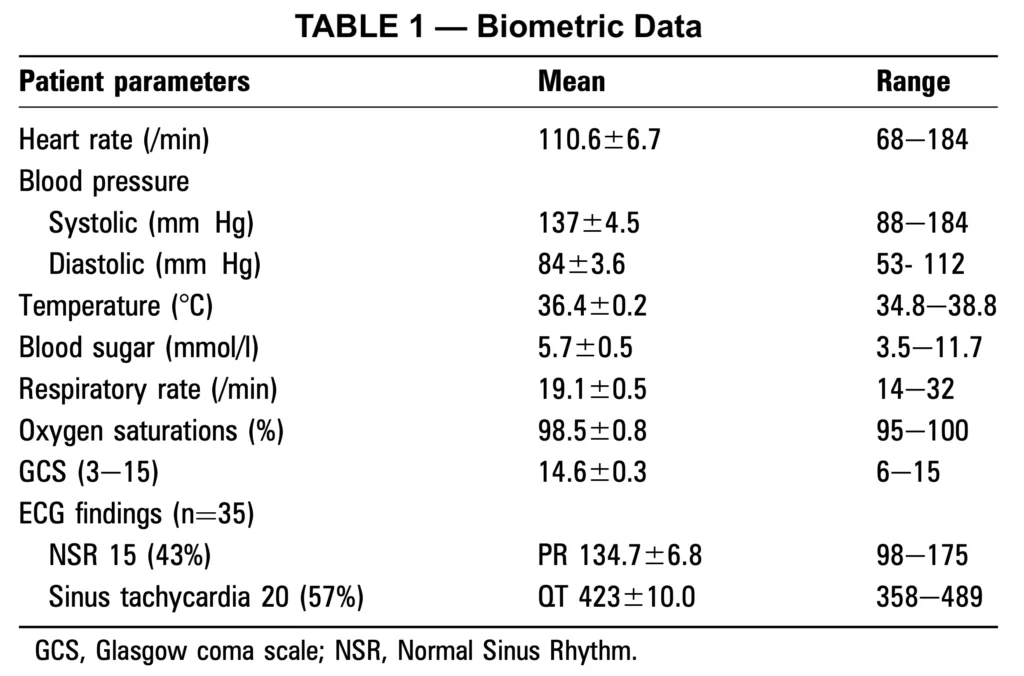

Patient demographics, duration of intake, quantity ingested, time taken before attendance, mode of arrival, reason for ingestion, co-ingestion of other substances, ECG findings, symptoms, blood results and disposal were recorded.

Subgroup analysis was performed comparing those who claimed to have taken mephedrone as a sole agent and those who had concurrently ingested alcohol. Statistical analysis was performed using F-test and then appropriate t-test was used to find out the significant differences between the two groups.

Mephedrone of toxicity: results of a study

Six articles were identified that related to cases of the potential clinical effects of mephedrone toxicity. Four articles related to single patient case reports, while one was a study interviewing 10 self-nominated mephedrone users. The final piece was a personal communication of hospital audit data referred to in the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs report on the consideration of cathinones.

The first case report comes from Sweden, where Gustaffsson and Escher describe the death of an 18-year-old girl in Stockholm. She had reportedly taken cannabis and mephedrone before becoming unconscious followed by cardiorespiratory arrest. Plasma screening was negative for other substances including alcohol, with mephedrone being the only substance detected at post mortem.

Wood et al described the case of a 22-year-old man who presented to a London city hospital. He admitted to taking 0.2 g of mephedrone orally followed by 3.8 g intramuscularly, while denying the ingestion of other substances. Symptomatically he had blurred vision, chest discomfort, diaphoresis and malaise. He was found to be hypertensive and mildly tachycardic. He was delusional, stating that he was suffering from mercury poisoning.

Serum and urine analysis with gas chromatography with mass spectrometric detection confirmed the presence of 4-methylmethcathinone at approximately a 0.15 mg/l concentration. Bloods including electrolytes, renal function and a mercury level were all normal. There were no other signs or symptoms of organ dysfunction and he was discharged after 6 h observation.

Toxicity of mephedrone: rare cases

Sammler reported in August a single case of a 15-year-old with a reduced level of consciousness following the ingestion of alcohol and what urine gas chromatography revealed to be mephedrone. Tests revealed a reduced serum sodium and osmolarity, an elevated cerebrospinal fluid opening pressure and an elevated urine osmolarity. Their presumptive diagnosis was of a mephedrone-induced euvolaemic hypoosmotic hyponatraemia with secondary encephalopathy and raised intracranial pressure.

The authors hypothesised a syndrome of inappropriate anti-diuretic hormone secretion similar to that found in some studies of ecstasy toxicity, but admitted to the relative confounding effects of excessive sweating and water intake in their individual case. In December the Lifeline charity in Middlesborough requested its publishing and research arm to conduct a study of the usage and effects of mephedrone so as to provide better advice to its clients.

Newcombe conducted structured interviews in three separate focus groups of six, two and two participants. All participants were over 18 years of age (nine men and one woman), and were polydrug users (including mephedrone). They had been identified by staff and agreed to answer questions for which they were rewarded with £20 on completion of the session.

Questions covered the context, consumption, effects, consequences and interventions of mephedrone usage. They admitted to usually mixing mephedrone with alcohol and other substances. They reported euphoria and hyperactivity as positive effects, with unwanted side-effects including visual disturbance, thirst, palpatations, myalgia, hallucinations and insomnia. No participants described themselves as addicted.

Discussion

This case series forms the largest such report describing mephedrone toxicity to date. The findings support those previously reported in individual case studies and also validate predictions of a psychoactive and cardiovascular toxicity pattern, similar to amphetamine and cocaine, as the likely presentation with mephedrone in overdose or regular usage.

The predominance of anxiety, chest discomfort and paraesthesia, with a not insignificant rate of collapse, seizures and confusion all contribute to a high admission rate (51%). It is noted that during the study period presentations related to other drugs of abuse were relatively small, only 31% of the number of mephedrone attendances even when cocaine, cannabis and heroin are combined together.

This may be due to the severity of symptoms but it may also reflect the drug’s usage by a naive population. Its ready availability as a «legal high» appeared to result in its usage by groups without experience of recreational substances. They may have been unprepared for symptoms and, tallied with its «legal» status, have been more willing to admit to its usage and seek help.

Our findings point to a pattern of addiction for this drug with patients reporting an inability to abstain after regular use. In addition, users describe bingeing until exhausting supplies or the severity of symptoms forced them to seek medical attention.

Although this work helps define the syndrome of mephedrone toxicity, we recognise that our qualification for subject inclusion was purely historical and lacked a formal objective test. We believe further study would be of benefit in defining the pathological effects of this drug in overdose. Any future study would ideally also contain provision for urine or plasma testing both to qualify inclusion and quantify levels in subjects enrolled.